!!UPDATE!!

This paper is now published at the Journal of Neuroscience and you can also find it here.

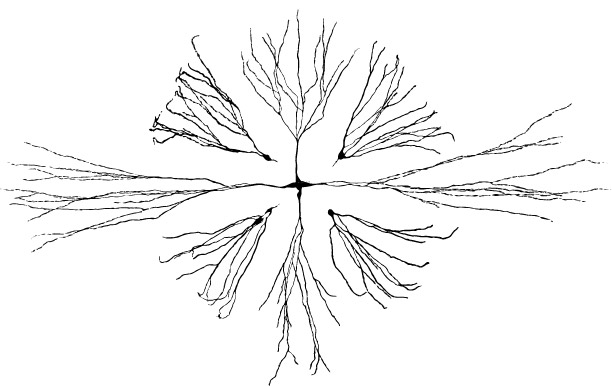

Congratulations to John Darby Cole and Delane Espinueva, two former undergraduate students who led an incredibly detailed study of the morphological development of adult-born neurons. You might read this and think, hasn’t this already been done? It’s true that people have looked at new neuron development but, amazingly, several key aspects are still not know. For example, since few people have examined adult-born neurons at older ages it was never really clear if or when new neurons stop growing (and thus, stop contributing developmental plasticity to the hippocampal circuit). Also, few have directly compared adult-born neuron morphology to neurons born in early development, so it is not entirely clear whether new neurons become the same as existing neurons, or might make up a distinct population. And the answer is….here is the preprint and here is the abstract:

During immature stages, adult-born neurons pass through critical periods for survival and plasticity. It is generally assumed that by 2 months of age adult-born neurons are mature and equivalent to the broader neuronal population, raising questions of how they might contribute to hippocampal function in old age when neurogenesis has declined. However, few have examined older adult-born neurons, or directly compared them to neurons born in infancy. Here, we used a retrovirus to visualize functionally-relevant morphological features of 2-to 24-week-old adult-born neurons in the rat. Two-week-old neurons had a high proportion of dendritic filopodia, small presynaptic terminals and an overproduction of distal dendritic branches that were later pruned, collectively indicating immaturity. From 2-7 weeks neurons grew and attained a relatively mature phenotype. However, several features of 7-week-old neurons suggested a later wave of growth: these neurons had larger nuclei, thicker dendrites and more dendritic filopodia than all other groups. Indeed, between 7-24 weeks, adult-born neurons gained additional dendritic branches, grew a 2nd primary dendrite, acquired more mushroom spines and had enlarged mossy fiber presynaptic terminals. Compared to neonatally-born neurons, old adult-born neurons had greater spine density, larger presynaptic terminals, and more putative efferent filopodial contacts onto inhibitory neurons. A model of extended development predicts that adult neurogenesis contributes to the growth and plasticity of the hippocampus until the end of life, even after cell production declines. Persistent differences from neonatally-born neurons may also endow adult-born neurons with unique functions even after they have matured.